Beneath the Neon: The Petty Insult That Ignited a Fatal Stabbing in Southampton’s Student Heartland

Southampton, England – December 10, 2025 – The fluorescent buzz of Portswood’s late-night takeaways had barely dimmed when, on the rain-slicked pavement of Belmont Road, a fleeting exchange of words escalated into a frenzy of steel and blood. It was the evening of December 3, the crisp bite of early winter mingling with the boisterous energy of freshers wrapping up their first term at the University of Southampton. Henry Nowak, an 18-year-old Essex transplant whose laughter could light up a lecture hall, had been toasting new beginnings with his football teammates at The Stile pub. Hours later, as the group spilled onto the street in high spirits, a trivial slight – a mumbled “watch it, mate” after a shoulder bump – would unravel into tragedy, leaving Henry dead from stab wounds to the chest and legs, and his accused killer, Vickrum Digwa, exposed in court with a motive so puerile it stunned the public gallery: a bruised ego over spilled chips.

The revelation came yesterday in the stark confines of Southampton Crown Court, where Digwa, a 22-year-old local with a wiry build and a history of minor scrapes, stood in the dock for the first time since his December 8 magistrates’ appearance. Flanked by his solicitor, the British-Asian delivery driver from St Denys Road offered no plea, his dark eyes fixed on the floor as Prosecutor Robert Salame laid bare the chain of events with clinical precision. “What began as an innocuous collision on a crowded pavement,” Salame intoned, his voice echoing off the oak-paneled walls, “devolved into a deadly dispute over nothing more than a packet of greasy fries.” Witnesses, including two of Henry’s teammates who had scarfed down late-night munchies from a nearby chippy, corroborated the account: as the group jostled past a cluster of locals outside the Golden Dragon takeaway, Digwa – nursing his own post-shift snack – felt a stray elbow nudge his paper bag. Chips scattered like confetti, and in the heat of the moment, Henry, ever the peacemaker with a pint-loosened tongue, quipped, “No harm, just a bit of a mess – clean it up yourself next time.”

To Digwa, those words landed like a gauntlet. “He took it personally,” Salame continued, citing Digwa’s post-arrest interview where the defendant admitted the remark “got under my skin” – a childish retort that festered into fury when Henry and his mates laughed it off, turning away to continue their banter. What followed was a textbook spiral of street bravado: Digwa, trailing the group by 20 paces, barked slurs in the drizzle, his voice cracking with the insecurity of a man twice Henry’s age but half his poise. Henry turned, hands raised in mock surrender, but the de-escalation fell flat. Digwa lunged, a concealed kitchen knife – the same serrated blade his mother would later attempt to bury – flashing under the sodium lamps. One thrust to the chest, piercing lung and heart in a crimson bloom; two slashes to the backs of the legs, hamstringing Henry as he crumpled, gasping, to the wet asphalt. “It was over a bag of chips,” Salame hammered home, his words drawing audible gasps from the back benches. “A petty grievance, amplified by alcohol and adrenaline, that cost a young man his life.”

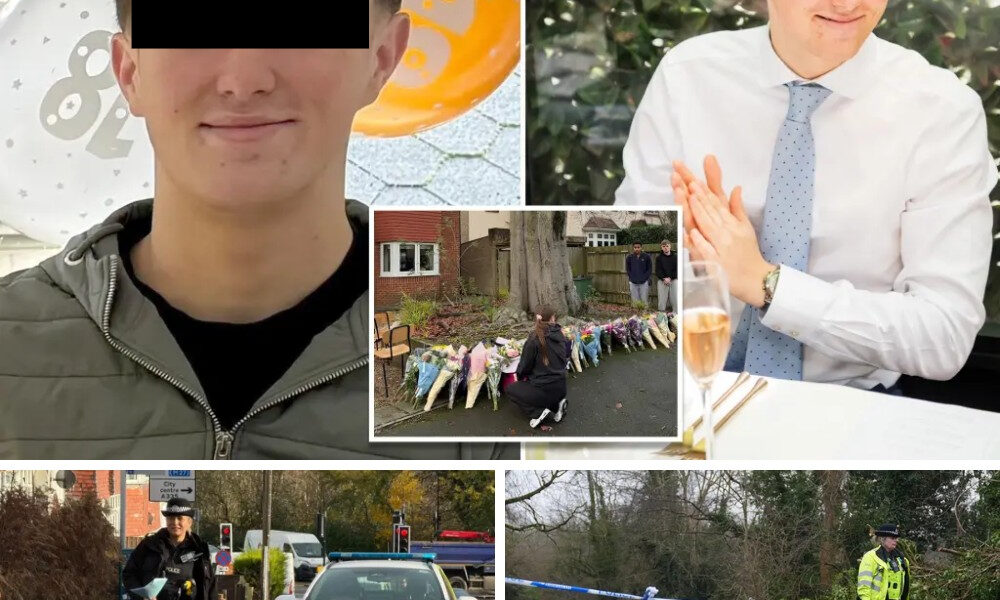

Henry Nowak wasn’t just another face in the fresher crowd; he was the spark that ignited dorm halls and training pitches alike. Hailing from the unassuming sprawl of Chafford Hundred in Essex, where commuter trains rumble past semi-detached homes and the Thames estuary whispers of bigger horizons, Henry had arrived at Southampton in September with the unjaded optimism of youth. A whiz at numbers – his A-levels in maths, economics, and business studies earning straight As that secured his spot in the accountancy and finance program – he balanced spreadsheets with sprints, juggling lectures on fiscal policy with twice-weekly football sessions. “He was the full package,” his father, Paul Nowak, a 48-year-old logistics manager with grease-stained overalls from years at the Ford plant in Dagenham, told reporters outside the family home last week, his voice thick with unshed tears. “Top grades, bottomless energy – he’d ring us after games, breathless, planning his next big thing. Never a dull moment with Hen.”

The night of December 3 marked the unofficial end-of-term bash for Henry’s squad – a mix of lads from the university’s premier and reserves teams, bonded over boggy practices at the Wide Lane Sports Ground and dreams of cup runs. The Stile, a no-frills boozer on Woodside Road with sticky floors and a jukebox stocked with Oasis anthems, had been their haven: pints of lager flowing, war stories from a recent 4-2 thrashing of Portsmouth Uni swapped like trophies. Henry, the Essex joker with a mop of sandy hair and a grin that crinkled his blue eyes, held court at the corner table, reenacting a botched free-kick with exaggerated flair. “He’d just nailed a assist in training that morning,” teammate Ollie Hargreaves, a lanky midfielder from Manchester, recalled in a candlelit vigil on campus Saturday night, his voice wavering under strings of fairy lights. “Talking about scouting weekends, maybe even semi-pro trials. We were buzzing – term one in the bag, Christmas back home. Then… this.”

As the clock neared last orders, the group tumbled out into the chill, scarves pulled high against the spits of rain, their chatter a defiant bubble against the night’s hush. Belmont Road, Portswood’s throbbing vein – lined with curry houses belching cumin-scented steam, off-licenses hawking cheap cans, and clusters of students weaving homeward – pulsed with the after-hours rhythm. Kebab wrappers skittered in the gusts, laughter ricocheted off Victorian terraces, and the distant thump of bass from upstairs flats underscored the scene. It was here, under the awning of the Golden Dragon, that fate intersected with folly. Digwa, wrapping a 10-hour shift ferrying naan and vindaloo for Uber Eats, had paused for his ritual post-work bite: a styrofoam tray of chips doused in vinegar and salt, the simple solace of a man scraping by on £9.50 an hour in a city where rents devour dreams.

The bump was accidental – Henry’s elbow grazing Digwa’s arm as the group squeezed past a gaggle of gigglers spilling from the door. Chips flew, vinegar splattered Digwa’s trainers, and the air thickened with awkwardness. Henry’s quip, meant as light-hearted deflection – “Watch your step, chip warrior” – landed amid chuckles from his mates, but to Digwa, it was mockery, a posh-kid slight from these out-of-towners invading his turf. “He felt small,” Salame quoted from Digwa’s taped confession, played in fragments for the court. “Like they were laughing at him, not with him. One comment, and it snowballed – ego over everything.” Digwa shadowed them for a block, muttering curses, until the boil-over at the Westwood Road junction: a shove, a shout, and the knife – pilfered from his mum’s kitchen drawer that afternoon, ostensibly for “protection” on late shifts.

Eyewitnesses painted a tableau of chaos frozen in time. A barista locking up the Espresso Junction next door described the “sudden scuffle” – shadows merging under the streetlamp, Henry’s cry of surprise cut short by the wet thud of blade on flesh. “It was so quick,” she told detectives, her hands still shaking as she recounted the blur. “One minute banter, next he’s down, clutching his side, blood pooling like spilled ink. His friends were screaming, phones out, but the attacker just… bolted.” Paramedics, screaming in at 11:32 p.m., fought a losing battle: chest compressions under the relentless rain, oxygen mask fogging with futile breaths. Henry was gone by 11:47, his university lanyard – emblazoned with “Future Finance Pro” – tangled in the tape that cordoned the scene by dawn.

The investigation, a whirlwind of forensics and frantic canvassing by Hampshire’s Major Crime Team, zeroed in on Digwa within 48 hours. CCTV from the Golden Dragon’s fisheye lens captured the chip spill in grainy glory: Digwa’s face twisting from annoyance to rage, the glint of steel as he pocketed the blade pre-shift. Phone pings placed him blocks away when sirens wailed, and a neighbor’s Ring cam snagged his frantic dash home to St Denys Road – a modest row of semis where curry aromas waft from open windows and kids kick footballs in the close. There, in the pre-dawn gloom of December 4, his mother Kiran Kaur – a 52-year-old NHS auxiliary nurse whose night shifts at Southampton General blurred into days of weary devotion – answered his pounding on the door. “Mum, I’ve done something stupid,” he allegedly gasped, thrusting the gore-smeared knife into her palm. Kaur, bleary-eyed in her uniform, didn’t hesitate: “Give it to me, son,” she whispered, stashing it under tea towels before scrubbing his clothes in the sink, her hands raw from the frenzy.

Raiders from the Major Crime Team descended at 6 a.m., the knife yielding Henry’s DNA under UV light, fibers from his Barbour jacket snagged on the serrations. Kaur’s charge – assisting an offender – stunned her community: a woman known for soup-kitchen shifts at the local gurdwara, her Facebook a gallery of family barbecues and Diwali lanterns. “She’s the rock,” a colleague at the hospital confided over tea in the canteen. “Baking for fundraisers, checking on the elderly. To hide evidence? It’s love gone wrong.” Digwa, by contrast, emerges as a portrait in quiet resentment: dropped out of sixth form at 17, bouncing between gigs – chip shop line cook, parcel courier – in a city where student influxes price locals out. No priors beyond a 2023 caution for affray outside a nightclub, but friends paint him as “hot-headed over nothing,” a lad whose pride simmered like vindaloo left too long on the hob.

Yesterday’s hearing, a procedural pivot to the crown court, crackled with the weight of the absurd. Salame’s dissection of the “immature trigger” – a spilled snack as casus belli – drew murmurs from the press benches, while Digwa’s barrister, Elena Patel, mounted an early defense: “My client regrets the heat of the moment, but self-preservation, not spite, drove his actions. A perceived threat in the dark, amplified by fear.” No trial date yet – remand to HMP Winchester for Digwa, bail with curfew for Kaur – but the ripple has reshaped Portswood. Extra patrols in hi-vis vests prowl the takeaways, “No Knives” stickers bloom on lampposts, and the university’s “Safe Socials” app pings de-escalation tips to freshers’ phones. Vice-Chancellor Professor Mark E. Smith, his address to the student union laced with sorrow, vowed “enhanced night buses and peer mediation hubs,” a nod to the 15 blade incidents campus-side since 2023.

For Henry’s family, ensconced in Chafford Hundred’s quiet cul-de-sacs, the motive’s banality is a fresh laceration. Paul’s tribute, read by a family friend at a memorial match Sunday – Henry’s reserves team edging a 2-1 win, balls placed at the center circle in his honor – captured the void: “Our boy, with his spreadsheets and silly dances, stolen over… chips? There’s no sense, just senseless loss.” His mother, Sarah, a primary school TA whose classroom now feels echoey without his volunteer storytime visits, added in a doorstep interview, rain streaking her face: “He called that morning, excited for the pub, the mates. ‘Mum, uni’s ace – wait till you hear about the penalty I saved.’ Now? Silence.” Siblings – little brother Tom, 14, clutching Henry’s Southampton scarf like a talisman – and the extended clan from Essex’s Polish roots (Nowak a nod to great-grandpa’s immigrant grit) have flooded GoFundMe with £45,000 for a bursary in his name: “Henry’s Headers,” funding kit for underprivileged kits.

Southampton, a port city etched with seafaring scars, absorbs the blow with weary resolve. Portswood’s multicultural mosaic – Punjabi delis cheek-by-jowl with Polish butchers, student co-ops abutting council estates – fosters fusion but frays at edges, where “town vs. gown” tensions simmer over parking spots and pint prices. Digwa’s community, tight-knit in St Denys’s Sikh circles, grapples with the stain: “He’s a good kid, lost his way,” an uncle murmured at evening prayers. Kaur’s arrest has sparked whispers of “family first” clashing with civic duty, her hospital shifts suspended pending trial. Broader, the case fuels the knife-crime chorus – 50,000 offences nationwide last year, per Home Office tallies, with Southampton’s tally up 12% amid post-Brexit youth displacements.

As December’s chill deepens, Belmont Road heals unevenly: chalk outlines faded, but wreaths of red-and-white scarves – Southampton FC colors Henry adored – linger like ghosts. Vigils swell, from the university’s Turner Sims auditorium (a screening of Bend It Like Beckham in his honor) to Essex kickabouts under floodlights. The “immature cause” – chips as catalyst – underscores a bitter irony: in a world of real stakes, the pettiest slights claim the brightest lives. For Henry, whose ledger balanced promise with play, the end was absurdly small. But his legacy? A ledger reopened – demanding dialogue over daggers, empathy over egos. In Portswood’s neon glow, one truth flickers: over spilled fries or fractured pride, we all teeter on the knife’s edge. Henry’s fall reminds us to step lighter, laugh louder, and – above all – clean up our messes before they multiply into mourning.